How to hunt: Detecting persistence and evasion with the COM

Editor’s Note: Elastic joined forces with Endgame in October 2019, and has migrated some of the Endgame blog content to elastic.co. See Elastic Security to learn more about our integrated security solutions.

After adversaries breach a system, they usually consider how they will maintain uninterrupted access through events such as system restarts. This uninterrupted access can be achieved through persistence methods. Adversaries are constantly rotating and innovating persistence techniques, enabling them to evade detection and maintain access for extended periods of time. A prime example is the recent DNC hack, where it was reported that the attackers leveraged very obscure persistence techniques for some time while they evaded detection and exfiltrated sensitive data.

The number of ways to persist code on a Windows system can be counted in the hundreds and the list is growing. The discovery of novel approaches to persist is not uncommon. Further, the mere presence of code in a persistence location is by no means an indicator of malicious behavior as there are an abundance of items, usually over a thousand, set to autostart under various conditions on a standard Windows system. This can make it particularly challenging for defenders to distinguish between legitimate and malicious activity.

With so many opportunities for adversaries to blend in, how should organizations approach detection of adversary persistence techniques? To address this question, Endgame is working with The MITRE Corporation, a not-for-profit R&D organization, to demonstrate how the hunting paradigm fits within the MITRE ATT&CK™ framework. The ATT&CK™ framework—which stands for Adversarial Tactics, Techniques & Common Knowledge—is a model for describing the actions an adversary can take while operating within an enterprise network, categorizing actions into tactics, such as persistence, and techniques to achieve those tactics. Endgame has collaborated with MITRE to help extend the ATT&CK™ framework by adding a new technique – COM Object Hijacking – to the persistence tactic, sparking some great conversations and insights that we’ve pulled together into this post. Thanks to MITRE for working with Endgame and others in the community to help update the model, and a special thanks to Blake Strom for co-authoring this piece. Now let the hunt for persistence begin!

Hunting for Attacker Techniques

Hunting is not just the latest buzzword in security. It is a very effective process for detection as well as a state of mind. Defenders must assume breach and hunt within the environment continually as though an active intrusion is underway. Indicators of compromise (IOC) are not enough when adversaries can change tool indicators often. Defenders must hunt for never-before-seen artifacts by looking for commonly used adversary techniques and patterns. Given constantly changing infrastructure and the increasingly customized nature of attacks, hunting for attacker techniques greatly increases the likelihood of catching today’s sophisticated adversaries.

Persistence is one such tactic for which we can effectively hunt. Defenders understand that adversaries will try to persist and generally know the most common ways this can be done. Hunting in persistence locations for anomalies and outliers is a great way to find the adversary, but it isn’t always easy. Many techniques adversaries use resemble ways software legitimately behaves on a system. Adversary persistence behavior in a Windows environment could show up as installing seemingly benign software to run upon system boot, when a user logs into a system, or even more clever techniques such as utilizing Windows Management Instrumentation (WMI). Smart adversaries know what is most common and will try to find poorly understood and obscure ways to persist during an intrusion in order to evade detection.

MITRE has provided the community with a cheat sheet of persistence mechanisms through ATT&CK™, which describes the universe of adversary techniques to help inform comprehensive coverage during hunt operations. It includes a wide variety of techniques ranging from simply using legitimate credentials to more advanced techniques like component firmware modification approaches. The goal of an advanced adversary is not just to persist - it is to persist without detection by evading common defensive mechanisms as well. These common evasion techniques are also covered by ATT&CK™. MITRE documented these techniques using in-depth knowledge about how adversaries can and do operate, like with COM hijacking for persistence.

To demonstrate the value of hunting for specific techniques, we focus on Component Object Model (COM) Hijacking, which can be used for persistence as well as defense evasion.

So What’s Up with the COM?

Microsoft’s Component Object Model (COM) has been around forever – well not exactly – but at least since 1993 with MS Windows 3.1. COM basically allows for the linking of software components. This is a great way for engineers to make components of their software accessible to other applications. The classic use case for COM is how Microsoft Office products link together. To learn more, Microsoft’s official documentation provides a great, comprehensive overview of COM.

Like many other capabilities attackers use, COM is not inherently malicious. However, there are ways it can be used by the adversary which are malicious. As we discussed earlier, most adversaries want to persist. Therefore, hunters should regularly look for signs of persistence, such as anomalous files which are set to execute automatically. Adversaries can cleverly manipulate the COM to execute their code, specifically by manipulating software classes in the current user registry hive, and enabling persistence.

But before we dive into the registry, let’s have a quick history lesson. Messing with the COM is not an unknown technique by any means. Even as early as 2005, adversaries were utilizing Internet Explorer to access the machine’s COM to cause crashes and other issues. Check out CVE-2005-1990 or some of CERT’s vulnerability notes discussing exactly this problem.

COM object hijacking first became mainstream in 2011 at the Virus Bulletin conference, when Jon Larimer presented “The Dangers of Per-User COM Objects.” Hijacking is a fairly common term in the infosec community, and describes the action of maliciously taking over an otherwise legitimate function at the target host: session hijacking, browser hijacking, and search-order hijacking to name a few. It didn’t take long for adversaries to start leveraging the research presented at Virus Bulletin 2011. For example, in 2012, the ZeroAcess rootkit started hijacking the COM, while in 2014 GDATA reported a new Remote Administration Tool (RAT) dubbed COMpfun which persists via a COM hijack. The following year, GDATA again presented the use of COM hijacking, with COMRAT seen persisting via a COM hijack. The Roaming Tiger Advanced Persistent Threat (APT) group reportedly also used COM hijacking with the BBSRAT malware. These are just a few examples to demonstrate that COM hijacking is a real concern which hunters need to consider and handle while looking for active intrusions in the network.

The Challenges and Opportunities to Detect COM Hijacking

Today, COM hijacking remains relevant, but is often forgotten. We see it employed by persistent threats as well as included in crimeware. Fortunately, we have one advantage - the hijack is fairly straightforward to detect. To perform the hijack, the adversary relies on the operating system to load current user objects prior to the local machine objects in the COM. This is the fundamental principle to the hijack and also the method to detect.

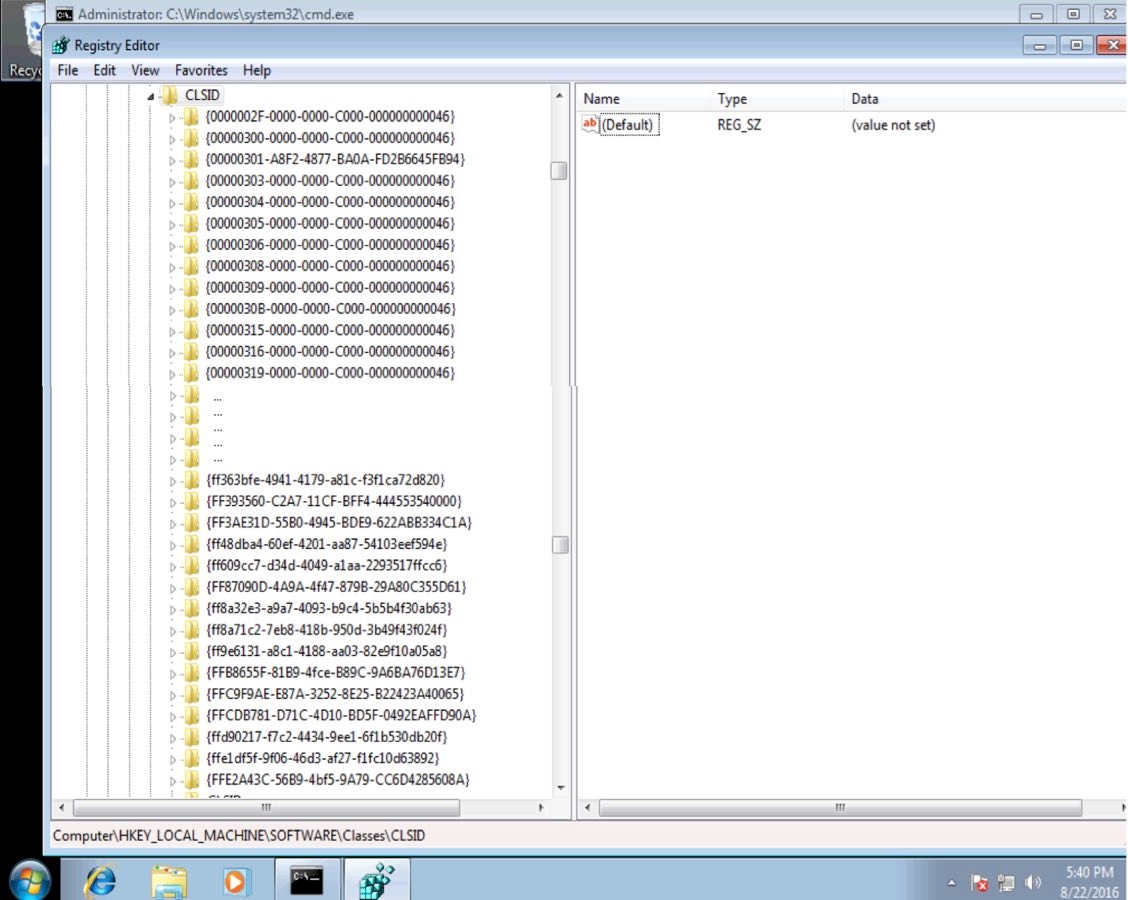

Easy, right? Well, there are some gotchas to watch out for. Most existing tools detect COM hijacking through signatures. A COM object is identified in the system by a globally unique identifier called a CLSID. A signature-based approach will only look at and alert on specific CLSIDs which reference an object that has been previously reported as hijacked. This is nowhere near enough because, in theory, any COM object and any CLSID could be hijacked.

Second, for us hunters, the presence of a user COM object in general can be considered anomalous, but some third-party applications will generate such objects causing false positives in your hunt. To accurately find COM hijacks, a more in-depth inspection within the entire current user and local machine registry hive is necessary. In our single default Windows 7 VM, we had 4697 CLSIDs within the local machine hive. To perform the inspection, you will need to dust off your scripting skills and perform a comparative analysis within the registry. This could become difficult and may not scale if you are querying thousands of enterprise systems, which is why we baked this inspection into the Endgame platform.

At Endgame, we inspect the registry to hunt exactly for these artifacts across all objects within the registry and this investigation scales across an entire environment. This is critical because hunters need to perform their operations in a timely and efficient manner. Please reference the following video to see a simple COM hijack and automatic detection with the Endgame platform. Endgame enumerates all known persistence locations across a network, enriches the data, and performs a variety of analytics to highlight potentially malicious artifacts in seconds. COM hijacking detection is one capability of many in the Endgame platform.

Conclusion

Persistence is a tactic used by a wide range of adversaries. It is part of almost every compromise. The choice of persistence technique used by an adversary can be the most interesting and sophisticated aspect of an attack. This makes persistence, coupled with the usual defense evasion techniques, prime focus areas for hunting and subsequent discovery and remediation. Furthermore, we can’t always rely on indicators of compromise alone. Instead, defenders must seek out anomalies within the environment, either at the host or in the network, which can reveal the breadcrumbs to follow and find the breach.

Without a framework and intelligent automation, the hunt can be time-consuming, resource-intensive, and unfocused. MITRE’s ATT&CK™ framework provides an abundance of techniques that can guide the hunt in a structured way. With this as a starting point, we have explored one persistence technique in depth: COM hijacking. COM hijacks can be detected without signatures through intelligent automation and false positive mitigation, getting beyond many challenges present if an analyst would need to find COM hijacks manually. This is just one way in which a technique-focused hunt mindset can allow defenders to detect, prevent, and remediate those adversaries that continue to evade even the most advanced defenses.